Attachment in Action: A Series on the Power of Connection - Volume I: The History of Attachment Science

Have you ever wondered why you feel panicky, with an intense urge to check your phone over and over when waiting for a text from someone you like? Or perhaps that is why you feel trapped like you need to escape, when a partner gets just a little too close for comfort? Maybe you’ve noticed how some people seem to have the magic formula to effortlessly navigate relationships with confidence and ease, while for you it just feels so hard.

The answer to these questions lies in the science of attachment. But what exactly is attachment? Attachment can be understood as the bond between a child and their primary caregiver/s, a powerful emotional relationship, or, as John Bowlby (more on him later) wrote, “lasting psychological connectedness between human beings” (1969). In essence, it all distills down to one important word… CONNECTION.

Now, if you ask me (and Queen Brené Brown), a connection is the meaning of life. …connection is why we’re here. It’s what gives purpose and meaning to our lives. This is what it’s all about. It doesn’t matter whether you talk to people who work in social justice, mental health, and abuse and neglect, what we know is that connection, the ability to feel connected, is -- neurobiologically that’s how we’re wired -- it’s why we’re here. (Brown, 2010).

For Volume I of this series, we will journey back to the roots of Attachment Theory. After all, what kind of psychodynamic therapist would I be if we didn’t start with the family of origin?

John Bowlby, an English physician born in 1907, is the “father” of attachment science. Through his work, he became fascinated by the behavior of children in a school for “maladjusted” boys. These boys’ varied reactions to their inadequate parenting led Bowlby to explore what we now understand as “avoidant” and “anxious” attachment styles (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016, p. 6). Bowlby also recognized the multigenerational impact of attachment, writing, “Thus it is seen how children who suffer deprivation grow up to become parents deficient in the capacity to care of their children and how adults deficient in this capacity are commonly those who suffered deprivation in childhood” (Bowlby, 1951, p. 533). In essence, Bowlby identified that inadequate parenting can lead to specific behaviors and characteristics and that this wounding is often passed down from generation to generation.

During his research, Bowlby put an ad in the newspaper for a research position and hired Mary Ainsworth, the “mother” of attachment theory. Ainsworth’s work, particularly the Strange Situation Procedure—an experiment observing separation and reunion behaviors between a child and their caregiver—gave birth to the three attachment styles we recognize today: “secure,” “anxious,” and “avoidant” (Ainsworth et al., 1978).

One of Ainsworth’s first doctoral students, Mary Main—the “auntie” of attachment science—identified a need for a fourth category, “disorganized” attachment. This style was particularly associated with children in adverse psychosocial environments, where responses did not fit neatly into the existing security/insecurity framework (Rutter et al., 2009, p. 530). Thus, the four primary attachment styles were established.

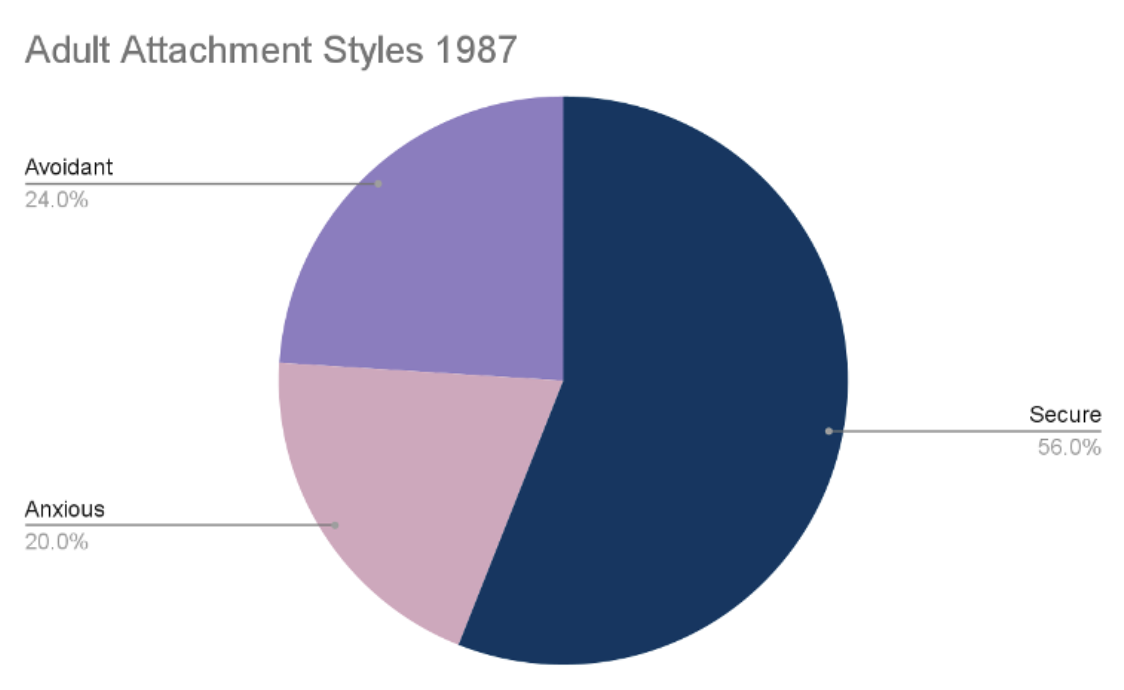

In 1987, researchers Hazan and Shaver expanded our understanding of attachment by exploring romantic love as an attachment process. They hypothesized that attachment styles remain stable into adulthood, and they were right (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). This discovery broadened the scope of attachment theory to encompass relationships far beyond the original child-caregiver dynamic.

Get ready to dive deep into Attachment in Action: A Series on the Power of Connection. Every other month, we’ll unpack the history, science, and transformative healing potential that understanding attachment offers. Don’t miss out—discover how to cultivate stronger, more meaningful connections with yourself and those who matter most. Your journey to deeper connection starts here!

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bowlby J. (1969). Attachment. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Loss. Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1951). Maternal care and mental health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 3(3), 355–533.

Brown, B. (2010, June). The power of vulnerability [Video]. TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/brene_brown_the_power_of_vulnerability?language=en

Hazan, C. & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 511–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022- 3514.52.3.511

Mikulincer, M. and Shaver, P. R. (2016). Attachment in adulthood (2 nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Rutter, M., Kreppner, J., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2009). Emanuel miller lecture: Attachment insecurity, disinhibited attachment, and attachment disorders: Where do research findings have the concepts? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(5), 529–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02042.x